Paragraphs in medical writing

Paragraphing

Paragraphs are essential divisions within a piece of extended writing, and in medical and scientific writing, this is no different. A paragraph can be considered any grouping of sentences which are united by an idea, logical argument, time sequence, or functional purpose. Generally, the sentences in a given paragraph should have a closer relation to the uniting theme in the paragraph they are in, (and thus the other sentences in this paragraph) than in any other paragraph found in the text. In this sense, a paragraph is a unit of meaning which is larger than the sentence, but smaller (or sometimes equal to) a section delineated by a heading or sub-heading. As such, the paragraph is a useful division, and proper paragraphing has a variety of functions and benefits that can significantly aid in the readability of a given text.

The primary function of a paragraph as a unit of meaning is organizational. If all writing is communication, then the text is the total meaning of this communication. It is impossible to impart this meaning to the reader all at once, in an unstructured whole. Paragraphing, then, is the means to which this total meaning can be divided and structured so that a reader can absorb the text sensibly. To use a metaphor, we cannot eat a whole chicken; a considerate cook will cut the chicken into manageable parts, and they will usually do so at the easiest points and into the most natural sections: the leg, wing, thighs, breast, neck, etc. These parts are the most recognizable to us, and we understand how they articulate with each other to form the whole chicken. In the same way, the paragraph forms not only semi-independent morsels of meaning but also both connects with the paragraphs surrounding it and has commonalities with other, more distant paragraphs in the text. A good writer, like a good chef, should prepare the meaning to be “digestible” and do so elegantly and along the most natural divisions: after all, we want to know what we are eating, and we want to understand what we are reading.

Another related but distinct advantage of proper paragraphing is the visual and aesthetic aspect, and in a similar sense, how the reader feels when reading your paper. Before they begin reading a text, readers will apprehend the “shape” of your article, and this shape will, for the most part, be determined by the paragraphs and consequent spaces you have chosen to arrange. If your article has a page of writing with no paragraphing—the dreaded “wall of text”—the reader will feel intimidated by such a challenge (1) and might give up before they get started. Conversely, if your text is striped with many short paragraphs and intervening spaces, the reader will be similarly daunted by the prospect of having to continually leap from one idea to the next. This is not to say that paragraphs cannot be very long or very short—they should be written to the length that the idea they express requires; overall, however, your paragraphing should keep in mind the mental capacity of your reader and the pace of reading which is most comfortable. Large paragraphs will require your reader to maintain attention on one idea for too long, and ask them to remember sentences too far back in the text, whereas paragraphs which are too short will require them to repeatedly shift focus, which can be equally exhausting.

A final point about the benefit of good paragraphing is that it should—if the paragraph itself is structured and well-written—enable for skimming and quick reference. If the first sentence of a paragraph is properly written and the subsequent sentences follow accordingly (this will be discussed more in-depth later), it should act as a label to indicate the general meaning of the rest of the paragraph. Given that interested readers might want to find a certain idea or specific piece of information from your text, proper paragraphing and paragraph writing will facilitate a quicker search of your text through a cursory glance by the reader at the first or perhaps the last sentence of the paragraph. If for example, they are looking for information on the incidence of pancreatic cancer in Asian populations, but the first sentence of your paragraph begins with a sentence about treatment outcomes in European patients, one can generally assume this paragraph will not contain the needed information. The reader can avoid wasting their time by reading the whole paragraph, and instead move on to search another paragraph for this information. Note again that if your paragraphs are generally very long or generally very short, the reader will either have to search intensively within one paragraph or search extensively over many different paragraphs; given this, one indication of good paragraphing and good paragraph writing is the ease and efficiency by which the information in it can be searched.

Structuring a paragraph

To fully gain the advantages of dividing your writing into paragraphs requires that each paragraph be structured and written properly. Before even beginning to put words on the page, it is important to have an idea of how your ideas will be sequenced, divided, and organized throughout your whole text. Once it is clear what the general outline of ideas and sub-ideas will be, it should be more apparent what idea each paragraph should communicate, and, once it is clear what the main idea of a paragraph is, the structure of that paragraph should follow. If you do not know what idea you want to express in your paragraph, the sentences in the paragraph will not have

The structure of a paragraph generally follows the following sequence:

Topic sentences are likely the most important part of a paragraph as they determine what the following sentences can include, and act as the “signpost” or label designed to aid the reader in quickly identifying the paragraph’s main idea. Therefore, in terms of content, the topic sentence should be broad enough in meaning to cover the ideas discussed by the following supporting sentences. On the other hand, they should be as specific enough to distinguish the paragraph as much as possible from the other paragraphs in the text, and most precisely inform the reader about the paragraph’s content. In terms of style, the topic sentence should be clear and to the point to most efficiently act as a paragraph reference. A complex or convoluted opening sentence will make it more difficult to quickly understand the contents of the paragraph. If you feel the need to elaborate upon the topic sentence extensively, consider using this information elsewhere in a later supporting sentence. A topic sentence can also clarify how the paragraphs relate to the previous paragraph (2) to increase the cohesion in the text, but this is not always necessary.

Supporting sentences should be related to the topic sentence in content, but should not be more general or broader in scope than the topic sentence. The supporting sentences should, in some way, develop or elaborate upon the idea introduced in the topic sentence depending on the type of paragraph you are writing. For example, if you are writing a descriptive paragraph, the supporting sentence will add more specific details; if you are writing a persuasive paragraph, the supporting sentences might provide logical proofs or real-world data; if you are writing a process paragraph, the supporting sentences will each describe a subsequent step in a procedure. There is always a temptation in writing these sentences to become distracted or over-elaborate and include details and information that are too specific or simply not necessary. To avoid doing this, always remember the main idea of your topic sentence paragraph while you write, and judge how closely each sentence you write remains within the topic sentence’s scope. Finally, try to connect these sentences using cohesive devices like transition phrases, pronouns, word repetition, and direct reference to the main idea. Doing so avoids having your paragraph read like a list of points, and instead makes one, unified, easy-to-read unit of meaning.

At last, while concluding sentences are not always necessary in a paragraph, they can perform a number of functions which significantly improve the readability of your writing. First, especially for long paragraphs, a concluding sentence can remind readers of earlier information in the paragraph, and indicate to them what the most essential or important points were in the paragraph. In logically complex or argumentative paragraphs, concluding sentences can provide the final implication of a complicated sequence of reasoning, or explain concisely how the supporting sentences prove the claim asserted in the topic sentence. Concluding paragraphs, similar to topic sentences, can also act as a bridge to the next paragraph so long as they also properly discuss the paragraph they are in (2).

Example paragraph writing

Below is a sentence-by-sentence analysis of a paragraph to show how a well-constructed paragraph can maintain

Sentence 1: topic sentence

The paragraph begins with the topic sentence. It is clear, to the point, and broad, identifying the major aspects of the paragraph topic—EGFR TKI’s, non-small cell lung cancer, and patients with EFGR mutations—without going into detail about any one of them. We expect the subsequent supporting sentences to elaborate on, in some way, one or more of these topics.

Sentence 2: supporting sentence

Indeed, the first supporting sentence goes into further detail about the evidence supporting TKI treatment. This maintains unity. Through repeating “TKI’s”, and using a pronoun with a noun, “these patients”, which refers to the NSCLC patients with EFGR mutations in the topic sentence, we know the concepts in the first sentence are being used again in the second sentence. This maintains cohesion.

Sentence 3: supporting sentence

The second supporting sentence maintains unity by referencing ideas from the topic sentence: “NSCLC”, “EFGR mutations”, and “TKI”. It develops the paragraph by expanding upon the guidelines and testing related to this therapy. Cohesion is maintained again by using a demonstrative pronoun plus repeating a noun, “their demonstrated efficacy”, referring to the TKI therapy trials of the previous sentence.

Sentence 4: supporting sentence

The third supporting sentence further develops the paragraph by discussing the sampling methods to test for EGFR mutation. Unity is maintained with the repetition of the words “NSCLC” and “EGFR-mutation”. Cohesion with the previous sentence is achieved through using the word “testing” which is the main focus of the previous sentence.

Sentence 5: supporting sentence

This sentence is closely related to the previous one (they can even be considered one sentence) and moves the discussion to the limitations of the sampling for EFGR mutation. The transition phrase, “As a result”, and repetition of “tissue/cytology samples” shows the logical connection with the previous sentence and thus maintains cohesion. Note that due to the easily understood connection between these two sentences, paragraph unity is maintained without the need to refer directly to the main topic again.

Sentence 6: concluding sentence

This concluding sentence further advances the discussion by outlining the research in different sampling methods for EGFR mutation. In this way, it acts as a transition or bridge to the next paragraph; we expect the next paragraph to discuss one more of these new sampling methods, and indeed it does. The concluding sentence also, however, maintains cohesion and unity. Through using “this limitation” and “sample”, it points to the previous sentence and the “restricting” of the sample quantity and quality, thus accomplishing cohesion. Through mention of “NSCLC” the reader is brought back to one of the main topics introduced in the topic sentence, and unity is preserved.

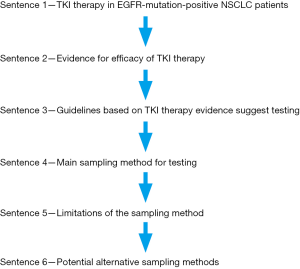

Overall, we can see how the topic is introduced in the first sentence and is gradually progressed in each sentence. The reader can follow this progression because the unity of theme and cohesion are respectively maintained through repetition or reference to the main topics, and transition words and pronouns in each sentence. We can see in Figure 1 how the paragraph develops in theme on a step-by-step basis.

Paragraphing for medical research articles

While the discussion in previous sections can be applied to academic writing in general, this section will consider how paragraphing can be applied to the typical characteristics of an original medical research article. Two aspects will be approached here: (I) how to determine where paragraph divisions should be made in-text, and (II) how to structure each paragraph according to what function they perform in the text. Note that these are mainly guidelines or recommendations and are by no means hard rules or formatting guides that must be strictly followed.

Paragraph divisions and functions

Both of these aspects depend on using the idea of different “

For illustration, one description of the functions and the IMRAD section of a research article they belong to are summarized in Table 1. Again, these are merely one version of how an article might be structured.

Table 1

| Section | Function | Possible paragraph type(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Background | Description/definition, compare/contrast |

| Literature review | Classification/analysis, narrative, compare/contrast | |

| Social impact | Argumentative, description | |

| Research problem statement | Process, description | |

| Methodology | Participants | Process, description |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Process, description | |

| Procedure | Process/narrative | |

| Statistical analysis | Process | |

| Results | Findings of procedures | Description |

| Findings of statistical analyses | Description | |

| Discussion | Principal findings | Description |

| Comparison with literature | Compare/contrast | |

| Interpretations & implications | Argumentative | |

| Limitations | Qualification | |

| Conclusion | Argumentative, description |

For the purposes of paragraphing, that is, dividing your writing into smaller units, each of the above functions can correspond to a paragraph or multiple paragraphs depending on the length or extensiveness of a given function. For studies with multiple research questions or multi-part methodologies, each of these questions or parts will naturally form paragraphs in the methodology and corresponding results section.

Paragraph types and functions

After determining how your article might be divided into paragraphs, a proper consideration of how a given paragraph might be structured can begin. Depending on the type of function the paragraph is performing, the structure of a paragraph can vary according to a different

Definition or description paragraph

This type of paragraph is useful for outlining the

Classification or analysis paragraph

Similar to a definition or description paragraph, this type of paragraph attempts to outline the features of a particular topic; however, it might discuss these parts in more analytical depth (4), and in a more critical fashion. This type of paragraph might actually be useful in the

Narrative or process paragraph

Narrative and process paragraphs are similar in that they both describe a sequence of events in time. The process paragraph is more concerned with outlining how to complete a process and is thus suited for the

Argumentative paragraph

An argumentative paragraph will use logical reasoning and consequence as the main means to arrive at or prove a conclusion and is more useful for discussing the

Compare/contrast paragraphs

This type of paragraph is best suited for discussion of literature either in the

Qualification paragraph

This type of paragraph will define the conditions under which a statement can be true, and delimit the applicability of certain assertions (4). Naturally, this is most useful for

Summary

Paragraphing is necessary for dividing your article into manageable units of meaning, providing a visually attractive and mentally comfortable structure for reading, and enabling an effective and easy referencing system.

Paragraphs should express a single idea and can be as long as that idea requires them to be. Despite this, the overall paragraphing should keep in mind the pacing and logic of the article.

Each paragraph should have structure, unity, and coherence. To accomplish this, paragraphs should start with a topic sentence which contains the main idea of the paragraph, supporting sentences which elaborate upon the topic sentence, and a concluding sentence which summarizes the essential meaning of the paragraph.

Paragraphs can be made according to the functions of a typical medical research article. Furthermore, they can be internally structured and conform to the typical linguistic features of the paragraph types for which they are most suited. These types include description, process, classification, argumentative, compare/contrast, and qualification paragraphs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, AME Medical Journal, for the series “Medical Writing Corner”. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/amj.2019.05.02). The series “Medical Writing Corner” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. JAG serves as a full-time employee of AME Publishing Company (publisher of the journal). The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Strunk W Jr, White EB. The Elements Of Style Illustrated. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Messuri K. Writing Effective Paragraphs. The Southwest Respiratory and Critical Care Chronicles 2016;4:86-8. Available online: https://pulmonarychronicles.com/index.php/pulmonarychronicles/article/view/290/719

- Denis MG, Lafourcade MP, Le Garff G, et al. Circulating free tumor-derived DNA to detect EGFR mutations in patients with advanced NSCLC: French subset analysis of the ASSESS study. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:1370-8. [Crossref]

- Procter M, Visvis V. Writing Advice Home. University of Toronto. Available online: https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/planning/paragraphs/

Cite this article as: Gray JA. Paragraphs in medical writing. AME Med J 2019;4:28.