Images in clinical medicine—bloodstream blindness: when fungi go rogue

Case presentation

A 71-year-old hypertensive, diabetic, male smoker with no significant ocular history was referred from the intensive care unit (ICU) to ophthalmology for intermittent visual disturbance associated with a high-grade pyrexia (39.9 ℃) during his ICU stay. One month prior, he underwent emergency abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair and subsequent Hartmann’s procedure for an ischaemic sigmoid colon.

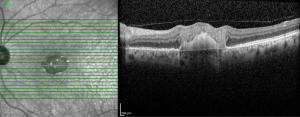

On ophthalmic examination, Snellen visual acuity was 6/12+1 (right) and counting-fingers (left) unaided. Pupil examination was normal. Both anterior segments were within normal limits. Fundus examination revealed fluffy-white chorioretinal lesions at both posterior poles, with a small right intra-retinal haemorrhage (Figures 1,2). Macular optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed bilateral vitreous haze, and on the left, a central foveal full-thickness hyperintense retinal lesion originating from the choroid (Figures 3,4).

Systemic investigations showed raised inflammatory markers [C-reactive protein (CRP) 216 mg/L, white cell count (WCC) 23.1×109/L, procalcitonin 13.15 µg/L], blood cultures positive for Candida albicans and significantly raised beta-glucan level (>500 pg/mL). His urine culture showed mixed growth. An autoimmune screen, total cholesterol profile and a trans-oesophageal echocardiogram were unremarkable.

This patient was diagnosed with bilateral endogenous fungal chorioretinitis with active left-sided central foveal chorioretinitis. He was treated with systemic fluconazole for approximately 8 weeks. He was initially considered for intravitreal antifungal injections due to central-vision involving disease, but the patient declined. Although the choroidal lesions eventually settled and his right visual acuity remained stable at 6/12, he developed irretractable foveal (central macular) scarring in the left eye. No further intervention could be considered, and the patient’s left visual acuity never recovered.

Discussion

Ocular candidiasis is a well-known complication of candidemia, via haematogenous fungal seeding of retina and choroidal blood vessels. The likely source for this patient is from his AAA graft, although other possibilities include his colon surgery, central-lines from his prolonged ICU admission and underlying diabetes.

Ocular candidiasis is usually treated with systemic antifungal therapy. If practical, the likely source(s) of the candidemia should be removed. In sight-threatening cases (e.g., macular involvement) or if the patient is not responding to systemic therapy, intravitreal antifungal injections and vitrectomy can be considered. To ensure an appropriate antifungal with good ocular penetration is used, liaison with the local microbiology team is advised.

Ocular candidiasis can present with eye pain, redness, photosensitivity, blurred vision and floaters. However, ICU patients may not be able to report ocular symptoms. Therefore, screening is required to prevent blindness. Where previously all patients with positive fungal blood-cultures were screened ophthalmologically, recent evidence indicates intraocular-disease needing/amenable to treatment is uncommon. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the Intensive Care Society jointly produced guidelines which state that routine ophthalmology screening for fungi-culture positive patients is no longer indicated, but should still occur on a case-by-case basis if the patient is either visually symptomatic, or unable to report symptoms, or has an abnormal eye appearance (e.g., hypopyon—a collection of pus in the anterior chamber). Vitreous cultures, performed by ophthalmologists, can aid diagnosis in equivocal cases.

However, in all cases of confirmed ocular candidiasis, thorough workup is strongly recommended to confirm the source of the candidemia as this can sometimes be the first presentation of disease in a patient.

Conclusions

- The eye may be involved in any fungaemia; this can be sight-threatening.

- Routine ophthalmology assessment of patients with fungaemia by ophthalmology is no longer always indicated, but must be sought in suspicious cases.

- A high index of suspicion is required, especially in ICU patients who are both high-risk and often unable to report visual symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a standard submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://amj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/amj-23-108/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://amj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/amj-23-108/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Cite this article as: Tan M, Sheth T. Images in clinical medicine—bloodstream blindness: when fungi go rogue. AME Med J 2024;9:40.